Since April 2013 tax residency in the UK has been determined by a number of tests collectively known as the Statutory Residence Test (‘SRT’). Prior to this, residency was based on case law and HMRC guidance. Although the SRT provides much greater certainty to individuals as to their tax position, there are still some elements of uncertainty.

Recent high-profile cases have highlighted the need to take proper care when considering one’s tax residency in the UK, as the consequences of misinterpreting the SRT can be significant. This article seeks to highlight some of the most common issues.

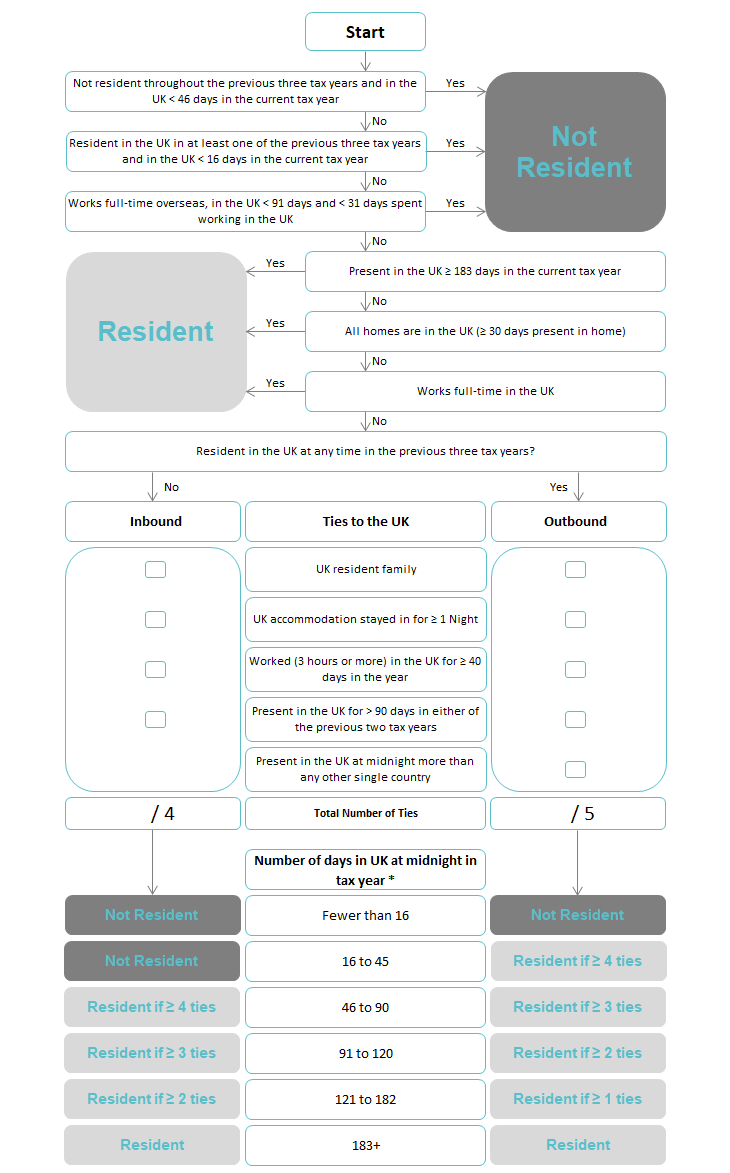

It is not the intention of this article to explain the SRT in detail, however, to provide context, the key rules have been outlined. Broadly speaking, the SRT is split into three parts: ‘automatic overseas tests’, ‘automatic UK tests’ and the ‘Sufficient ties test’. The principal factor in the tests is the days spent here, which is usually a day where the individual is in the UK at midnight, however other factors such as work and homes are also relevant.

In practice, an individual will first consider the automatic overseas tests and, if none are met, consider the automatic UK tests and ultimately the sufficient ties test. The rules are summarised in the flowchart below.

In the extreme, an individual is not resident under the SRT if, for any given UK tax year (ended 5 April), they are here for less than 16 midnights and resident if they are here for greater than 183. Between those extremes, residency will depend on the precise circumstances of that individual.

Some of the aspects of the test are quite straightforward, however, problems that are encountered in practice are:

1) The SRT includes various tests which consider historic residency. To correctly determine residency for a given year you may need to consider the residency position for the three preceding tax years.

2) The working full-time overseas test requires an individual works ‘sufficient hours overseas’, as defined by several complex steps. The ‘headline’ rate of 35 hours a week on average may be achievable for many, however, care is required, particularly where there is a change in employments which could lead to a significant break from work.

3) Various parts of the SRT consider UK work (which is not restricted to employment) records should be kept determining what is a UK workday and, perhaps more importantly, when a UK day is not a workday.

4) The definition of a ‘home’ is wide and relevant to various parts of the SRT. Having your only home in the UK can make you UK tax resident in as little as 30 days. It is very important to understand what can be considered a home – both in the UK and overseas.

5) In some circumstances working in the UK for even a single day can trigger automictic residence for the year. This test can look at the following 365 days so may require a degree of forward planning.

6) Residency usually applies to an entire tax year, therefore, subject to ‘split year’ provisions, an individual could be resident prior to their arrival – or after they have left. The split year provisions are very prescribed and usually have conditions relating to the preceding or following tax years. In particular, care needs to be taken regarding how much time is spent in the UK after departure or prior to arrival.

7) Although generally the SRT considers a UK day as one where the individual is here at midnight, certain ‘deeming rules’ can treat part days as days of residence. The deeming rule can apply to individuals who have been resident in the UK in one of the previous three tax years and who have at least 3 sufficient ties to the UK.

8) The SRT includes complex anti-avoidance provisions which can treat certain sources of income and gains as being taxable if the individual becomes UK tax resident within 5 years or less of breaking UK tax residency. For these special rules not to apply, the individual’s period of non-residence must exceed 5 years, that is, a minimum period of five years plus 1 day. In practice this often means an individual needs to be non-resident for six years.

9) The SRT provides that potentially up to 60 days can be excluded from the day count where those days relate to exceptional circumstances. It is apparent from the legislation and recent tribunal hearings that exceptional in this context pertains to matters outside the taxpayer’s control, such as natural disasters, lockdowns, etc. Those hoping to rely on personal exceptional circumstances can expect a challenge from HMRC.

10) Other legislation can override the SRT; a topical example is the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 (which treats members of the House of Commons and House of Lords as resident in the UK for tax purposes no matter how many days they spend in the UK).

The consequences of being unintentionally UK tax resident can be significant. As well as impacting the taxpayer’s income tax liability for the particular year, it could also trigger anti-avoidance provisions resulting in taxes being payable for earlier years. For those who are not domiciled in the UK, a year of residency could potentially impact their deemed domicile status and consequently their exposure to UK taxes (including Inheritance Taxes) on foreign income and assets.

If tax residency is triggered, it is necessary to consider other mitigation to avoid surprise tax liabilities.

In many instances the impact of being UK resident can be negated by UK law or the use of the UK’s network of double tax treaties. Indeed, in some circumstances the double tax treaty may effectively override the UK tax residency position.

It is important to note that in certain instances, a liability to UK tax arises regards of tax residency. Common situations include where a non-resident individual performs employment duties in the UK that are not otherwise exempt by a double tax treaty, or the sale of UK property or certain property holding companies.

Please do not hesitate to get in touch if you would like to find out more.

We’d love to hear from you. To book an appointment or to find out more about our services: